At the last World Congress of Dermatology, our colleague, Vanessa Schmidt, who practices at the University of Liverpool, discussed spontaneous feline alopecia, which is rarer than self-induced alopecia and whose etiological diagnosis is sometimes complex.

Spontaneous feline alopecia is a relatively rare phenomenon characterized by hair loss not attributable to self-trauma. Various inflammatory and non-inflammatory processes can be involved, making its diagnosis complex and requiring a systematic and dichotomous approach. Understanding the responsible mechanisms requires a detailed history, a thorough clinical examination, and a series of wisely selected complementary investigations.

1 Differential Diagnosis of Spontaneous Feline Alopecia: The importance of history and clinical examination

The differential diagnosis of spontaneous feline alopecia relies on a rigorous approach, starting with the history and clinical examination. The initial objective is to establish whether the alopecia is truly spontaneous or a result of self-trauma.

1.1 Exclusion of self-trauma: A critical step

Before any other etiological consideration, it is crucial to formally rule out self-trauma. The owner’s interview must be precise and exhaustive, focusing on several key points:

- Presence of hair in the domestic environment (furniture, carpets, etc.). A significant amount of hair found outside the cat’s coat suggests self-trauma.

- Coat quality and saliva traces: Evaluation of the general quality of the coat (sparse coat, thinning coat, areas of abnormally short coat or absence of hair) and search for traces of excessive saliva on the skin.

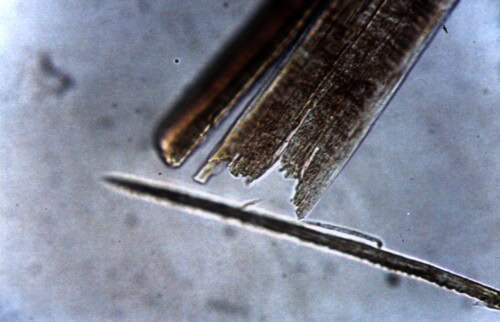

- Trichogram: Microscopic analysis of hair (trichogram) can identify hair fractures, abnormalities in hair structure (cuticle, cortex, or medulla abnormalities).

Photo 1: Trichogram showing a broken hair

However, the absence of these signs is not enough to rule out self-trauma. A cat can be extremely discreet and the signs can be subtle or transient.

1.2 Characterization of Alopecia: Location, extent, and symmetry

The precise description of alopecia is a key element in diagnostic orientation. Several aspects should be noted:

- Location: Is the alopecia localized to the head, flanks, belly, limbs, tail, or is it generalized? A particular location can suggest specific causes. For example, facial alopecia may be linked to dermatophytosis, while symmetrical trunk alopecia may be associated with endocrinopathy.

- Extent: Is the alopecia partial, total, focal (localized to a small area), multifocal (several distinct areas), or diffuse (spread over a large area)? The extent of alopecia provides information on the severity and extent of the underlying disease.

- Appearance: Is the appearance of the alopecia regular, irregular, symmetrical, or asymmetrical? Irregular patterns suggest localized and external skin conditions (infections, allergies, parasites), while symmetrical patterns are more often associated with systemic diseases (endocrinopathies, metabolic diseases).

The cat’s age at the onset of symptoms is also crucial. Certain conditions, such as congenital alopecias, appear in young cats, while endocrinopathies more frequently affect middle-aged to older cats.

1.3 Anamnesis: Essential information for an etiological diagnosis

Anamnesis plays a crucial role in diagnostic orientation. It is important to systematically collect the following information:

- Exposure to infectious agents: Any history of contagion or zoonosis (e.g., contact with other sick cats, stay in a kennel or shelter, exposure to wild animals) must be carefully explored.

- Travel history: Recent travel may expose the cat to exotic diseases and should be taken into account.

- Clinical signs suggesting systemic disease: Search for clinical signs suggesting systemic disease (weight loss, lethargy, polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, vomiting, diarrhea…) that could be at the origin of the alopecia. For example, significant weight loss associated with alopecia may suggest neoplastic disease.

- Medication history: Medication history is essential to identify possible hypersensitivity reactions or medication side effects that may cause alopecia. Prolonged corticosteroid therapy, for example, can induce atrophic alopecia.

2. Diagnostic Approach

After a detailed history and a rigorous clinical examination, complementary examinations are necessary to confirm or rule out diagnostic hypotheses.

2.1 Immediate complementary examinations: Cytology, Culture, and Hematological Analyses

Initial investigations include:

- Cytology: Cytological examination of a skin sample can reveal microorganisms (bacteria, yeast, parasites) or inflammatory cells. Lymph node fine-needle aspiration can also be useful, particularly in cases of suspected lymphoma.

- Mycological culture: In case of suspected dermatophytosis, fungal culture on appropriate media is essential to isolate and identify the responsible dermatophyte. The use of Wood’s light can facilitate preliminary identification of fluorescent dermatophytes such as Microsporum canis. PCR can also be used to detect fungal DNA.

- Hematological analyses: A complete blood count can detect blood abnormalities that might suggest systemic disease or immune deficiency.

- Blood biochemistry: A complete biochemical profile provides information on the function of various organs (liver, kidneys…) and can detect possible metabolic abnormalities.

- Urinalysis: Urinalysis is crucial in evaluating kidney function and the presence of potential urinary tract infections. Cytological and bacteriological analysis can also reveal useful information.

- Hormone tests: In case of suspected endocrinopathy (hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, hyperadrenocorticism), specific hormone tests are necessary. Evaluation of thyroid function, cortisol concentration, and insulin is often useful in this context.

2.2 Delayed and semi-delayed complementary examinations: Histopathology and Imaging

If initial investigations do not lead to a diagnosis, more advanced investigations are necessary.

- Histopathology: Histological examination of a biopsied skin sample is crucial for analyzing tissue structure, identifying the types of inflammatory cells present, characterizing lesions, and confirming or ruling out the diagnosis. Histopathological analysis can reveal typical changes in certain specific skin diseases.

- Imaging: Depending on the clinical suspicion, medical imaging (radiography, ultrasound, computed tomography, MRI) may be required to detect tumors or organ abnormalities. Abdominal ultrasound is particularly important in the diagnosis of pancreatic or biliary neoplasms frequently associated with paraneoplastic alopecia.

4 Etiologies of non-self-induced alopecias

The classification of spontaneous alopecia into inflammatory and non-inflammatory causes, although useful, should not obscure the possibility of overlap between these categories, particularly depending on the chronicity and evolution of the disease.

4.1 Inflammatory Causes

Inflammatory causes of spontaneous alopecia in cats involve an infiltration of inflammatory cells within hair follicles and associated structures. Several conditions are frequently encountered:

Dermatophytosis: Primarily caused by Microsporum canis, this highly contagious mycosis has significant zoonotic potential. Clinical signs are variable, ranging from localized alopecic patches, often accompanied by scales, crusts, and pruritus, to more generalized forms. Predominant localization on the head, face, ears, limbs, and tail is common, but more diffuse lesions are possible. Certain breeds, such as Persians and Maine Coons, seem predisposed. The infection reservoir includes clinically affected cats, healthy carriers, and environmental spores that can remain viable for several months. Microscopic examination (direct examination, trichograms), fungal culture, and PCR are the reference examinations to confirm the diagnosis. The use of Wood’s lamp, although often recommended for rapid detection of fluorescence, should be interpreted with caution, as fluorescence is not always present and can be falsely negative depending on the type of dermatophyte.

Photo 2: Extensive feline ringworm

Demodicosis: Caused by Demodex cati, this parasite, however, is rare in cats, generally associated with underlying immunosuppression. Infections with Feline Immunodeficiency Virus (FIV), Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV), diabetes mellitus, hyperadrenocorticism, or even Bowel-associated in situ carcinoma (BISC) can be predisposing factors. Lesions are often localized to the head, ears, or neck, characterized by alopecia, erythema, crusts, and scales. Pruritus is variable. Immunosuppression leads to uncontrolled proliferation of the parasite, leading to a greater extension of lesions. Diagnosis relies on the demonstration of the parasite by deep skin scraping and microscopic examination.

Exfoliative Dermatitis Associated with Thymoma: A rare paraneoplastic syndrome, it manifests as generalized exfoliative erythroderma, often preceding systemic signs associated with thymoma. The pathophysiology involves activation of autoreactive T lymphocytes. Alopecia, often generalized, is associated with significant secondary pruritus to lesions if they are infected. Diagnosis requires skin biopsy and thoracic imaging to search for the primary tumor.

Other inflammatory dermatoses: Other inflammatory conditions can manifest as alopecia, including folliculitis, sebaceous adenitis, pyoderma (bacterial skin infection), or cutaneous lymphomas. Each condition has its specific clinical and histopathological characteristics that guide the differential diagnosis.

4.2 Non-Inflammatory Causes

Non-inflammatory causes often result from dysfunctions of the hair cycle or abnormalities in the synthesis of hair follicle components:

-

Paraneoplastic Alopecia: Rare condition, often associated with pancreatic or biliary tract tumors. It is characterized by generalized alopecia, shiny skin, and sometimes involvement of the paw pads. Systemic signs such as weight loss and polyphagia are common. Diagnosis relies on abdominal imaging and skin histology showing follicular atrophy.

-

Hyperadrenocorticism (Cushing’s Disease): Frequently of pituitary origin (pituitary adenoma), it is often associated with insulin-resistant diabetes mellitus. Alopecia is frequently truncal, and the skin is fragile and prone to tearing and bruising. Systemic clinical signs, such as polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, weight loss, are predominant. Diagnosis relies on hormone assays (ACTH, cortisol) and sometimes on stimulation or suppression tests.

-

Hypothyroidism: Less common than hyperadrenocorticism, it can induce diffuse alopecia and dry skin. Other clinical signs, such as lethargy, obesity, and bradycardia, are also found. Diagnosis relies on blood thyroid hormone (T4) assay.

- Other non-inflammatory causes: Other less frequent causes of non-inflammatory alopecia exist, such as congenital alopecias, sebaceous gland dysplasias, or telogen effluvium (hair loss in the telogen phase).

5 Clinical Cases Illustrating the Diagnostic Approach

The following examples illustrate the diagnostic approach in cases of spontaneous feline alopecia.

5.1 Case 1: Sylvester, a Cat with Generalized Dermatophytosis

Sylvester’s story highlights the importance of a systematic exploration, even in the presence of seemingly simple symptoms. Dermatophytosis, although initially localized, can evolve into a generalized form, particularly in immunosuppressed cats. His hyperthyroidism and kidney failure also played a role in the severity of his condition. Close monitoring of these parameters is essential for the optimal management of his treatment. The effectiveness of antifungal treatment combined with the treatment of underlying conditions highlights the need for a multimodal approach in the management of this type of clinical case.

5.2 Case 2: Buster and Demodex cati Associated with Lymphoma

Buster’s case highlights the impact of immunosuppression on the clinical presentation of skin conditions. Immunosuppression induced by lymphoma and chemotherapy favored the development of an infestation by Demodex cati, which is usually commensal and non-pathogenic in immunocompetent cats. This case underscores the importance of considering immune status when interpreting results and implementing treatment.

5.3 Case 3: Stanley and Exfoliative Dermatitis Not Associated with Thymoma

Stanley’s case illustrates the importance of skin biopsy in the precise diagnosis of exfoliative dermatitis. Although exfoliative dermatitis is often associated with thymoma, it can occur in other contexts. The exclusion of a thymoma by imaging underscores the importance of a complete and rigorous diagnostic approach, integrating several investigation techniques. The detailed description of histopathology and imaging results is essential in the evaluation of this case.

5.4 Case 4: Chloe and Paraneoplastic Alopecia

Paraneoplastic alopecia is a rare but important cutaneous manifestation of certain malignant tumors. In Chloe, the association of alopecia with systemic signs such as weight loss, diarrhea, polyphagia, and lethargy guided the diagnosis towards an underlying neoplasm, revealed by ultrasound. The use of ultrasound or other medical imaging techniques is essential in the evaluation and management of paraneoplastic alopecia.

5.5 Case 5: Iatrogenic Hyperadrenocorticism and Side Effects

Iatrogenic hyperadrenocorticism, induced by prolonged or poorly managed corticosteroid therapy, is a significant cause of non-pruritic atrophic alopecia, highlighting the need to carefully monitor the side effects of corticosteroid treatments. Short-term corticosteroid therapy is often necessary, but must be followed by a gradual and controlled withdrawal to avoid complications. The described clinical case illustrates its distinctive impact and should therefore be considered during differential diagnosis.

6. Conclusion and Recommendations

Spontaneous feline alopecia represents a major diagnostic challenge. A methodical approach, integrating a detailed history, a complete clinical examination, and a judicious combination of complementary investigations, is essential to establish an accurate diagnosis and implement appropriate treatment. The cat’s age, the location, extent, and symmetry of the alopecia, the presence or absence of pruritus, as well as the cat’s medical history are key pieces of information. The presented clinical cases illustrate the complexity of differential diagnosis and underscore the need to adapt the diagnostic strategy based on clinical signs. Further research is necessary to improve the understanding of the mechanisms involved in certain alopecias and optimize their management.