Alopecia is one of the main reasons for consultation in canine dermatology.

Author: William Bordeau

Exclusive Dermatology Consultant

VetDerm Practice,

1 avenue Foch 94700 MAISONS-ALFORT

It can have many causes, as presented by Professor MECLENBURG at the last congress of the European Society and College of Veterinary Dermatology, which was held jointly with the annual GEDAC meetings, in Nice.

He particularly emphasized follicular dysplasias and dystrophies that can cause alopecia. In this regard, he reiterated the differences between these two terms, which are often confused, especially because the pathogenesis of certain dermatoses is unknown. Simply put, dysplasia is an anomaly of hair development without a trophic problem, while in dystrophy, hair anomalies result from nutritional disorders. However, there is still controversy regarding the classification of certain alopecias as dysplasias, dystrophies, or even follicular atrophies, knowing that, in addition, several phenomena can be associated.

Different classifications of canine alopecias exist. They can notably be distinguished as self-induced and spontaneous alopecia, even if the distinction is not always obvious. Professor MECLENBURG chose a somewhat unusual classification, wishing to differentiate alopecias of inflammatory origin from those that were not of inflammatory origin.

Concerning non-inflammatory alopecias, they can be separated into alopecias of genetic origin, which can be congenital or not, and acquired alopecias.

Concerning hereditary non-inflammatory alopecias, we notably have ectodermal dysplasias. These are well known in humans, and there are currently nearly 200 of them, including anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia which results from a perturbation of ectodysplasin receptors. They cause increased fragility of the hair shaft, which will rapidly lead to its fracture and the appearance of alopecia. These dysplasias can be associated with other anomalies, including dental ones. These ectodermal dysplasias can be congenital. Certain breeds are well known for having this type of alopecia, notably the Mexican hairless dog or the Chinese crested dog. These alopecic breeds are more prone to frostbite, solar dermatitis, and squamous cell carcinomas.

There are also certain hair dystrophies that result from anomalies located only in the follicles. Some are congenital, notably trichorrhexis nodosa, medullary trichomalacia, or pili torti, which have been exceptionally described in dogs.

Some alopecias can also result from a neuroectodermal dysplasia which will then cause a melanocyte anomaly. Indeed, melanocytes have a neuroectodermal origin. Here we can classify dilute coat dysplasia and black hair follicular dysplasia. These are clinically very similar dermatoses that may just be the same genodermatosis, but with different clinical expressions, with black hair follicular dysplasia appearing earlier. Dilute coat alopecia is the main genodermatosis in dogs. It has been described in blue and fawn coated dogs of various breeds. The progressive and extensive alopecia of diluted areas begins between 6 and 12 months.

Photo 1: Pattern alopecia in a Pinscher

We also have genetic alopecias that result from follicular atrophy. An anomaly of the hair cycle is observed, which translates into a shortening of the anagen stage or a lengthening of the telogen stage. They are not always associated with a morphological alteration of the hair follicle or the hair shaft. Here we can classify pattern alopecia, which is a rare dermatosis with 3 types depending on the breed and the location of the alopecia on the animal.

It appears from the age of 6 months, and results in 5 to 10 years in bilateral and symmetric alopecia. There is also canine recurrent flank alopecia which, as its name indicates, essentially affects the flanks, even if other locations can be affected. It is seasonal and therefore recurrent, even if in some cases the dermatosis passes a year, but at the extreme it can also be persistent.

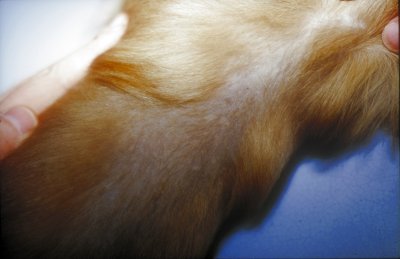

Photo 2: Dilute coat alopecia that could strongly suggest flea allergy dermatitis

There are also follicular dysplasias that are not cyclical. This concerns various breeds such as the husky or malamute, and the alopecia, which progresses slowly, will affect different areas of the body depending on the breed.

Apart from these hereditary alopecias, we must now consider acquired alopecias, which are also very numerous.

Thus, there are many alopecias that result from a localized anomaly in the hair cycle. Unlike the first category, they are generally reversible. This includes telogen effluvium, which results from the synchronization of hairs in the telogen phase following various phenomena, particularly intense stress.

We also have all the alopecias that result from dysendocrinia and are now well identified, for the most part. These are alopecias secondary to hypothyroidism, Cushing’s syndrome, or a sex hormone disorder.

After considering non-inflammatory alopecias and therefore those for which no primary inflammation existed, inflammatory alopecias must be considered. The latter should be separated into inflammatory alopecias of infectious origin and those that are not.

Concerning alopecias of infectious origin, these are all causes of folliculitis. Namely bacterial, dermatophytic, and demodectic folliculitis. Some viruses can also cause alopecia, notably poxvirus.

Alopecias that are not of infectious origin mostly have a dysimmune origin, and they are generally associated with mural folliculitis, i.e., the presence of inflammatory cells in the follicular epithelia and not in the lumen. In these alopecias, we find notably sebaceous adenitis, pemphigus foliaceus, mycosis fungoides, lupus erythematosus, erythema multiforme, and alopecia areata. In this subgroup, certain dermatoses are associated with follicular atrophy, including dermatomyositis, traction alopecia, and post-injection alopecia.

This article shows the multiplicity of causes of canine alopecias, and therefore the difficulty in determining their etiology. However, it is important to remember that only the identification of the underlying cause will allow its complete resolution, if indeed that is possible.

Bibliography

Meclenburg L. Hair follicle dysplasia and dystrophy or the multiple forms of alopecia in the dog. 2002, Proceeding GEDAC/ESVD/ECVD congress, Nice, pp 19-22

Casal & coll. X-linked ectodermal dysplasia in the dog. 1997, J. Hered., Vol. 88, pp 513-517.

Guaguere E. Les alopécies génétiques chez le chien. 2001, CES Dermatologie, Nantes.

L Ordeix, MD Fondevila, L Ferrer, A Fondati. Traction alopecia with vasculitis in an Old English sheepdog. Journal of Small Animal Practice, 2001, Vol 42, Iss 6, pp 304-305