Yeasts of the genus Malassezia constitute lipophilic fungal agents that have evolved as cutaneous commensals and opportunistic pathogens across various mammalian and avian species. Their involvement in canine and feline dermatological and otological conditions represents a daily clinical challenge for veterinary practitioners on a global scale. At the recent NAVDF congress in Orlando, our colleague Ross Bond, a world specialist on the subject, had the opportunity to provide a comprehensive update, covering pathogenic, diagnostic and therapeutic aspects.

History and taxonomy of Malassezia yeasts

The association between Malassezia yeasts and canine otitis externa dates back to the pioneering work of Bengt Gustafson, who published his thesis in Stockholm in 1955 on 201 cases of predominantly acute otitis externa in dogs. The Cocker Spaniel constituted the most represented breed in this study, and it remains remarkable that this breed predisposition is still recognisable in contemporary clinical practice. Gustafson isolated yeasts alone in 108 cases and yeasts associated with staphylococci in the majority of the remaining cases, an observation that practitioners performing daily cytology would immediately recognise as familiar.

He observed that the frequency of yeasts decreased in chronic cases, giving way to Proteus and Pseudomonas infections, a finding with which the contemporary veterinary community would unanimously agree. Of 97 healthy ears examined, he detected only slight yeast growth in eight cases only. The morphological characteristics of these yeasts — oval shape, polar budding, absence of mycelium, slow growth and absence of fermentation — led Gustafson to link them to the genus Pityrosporum, now designated Malassezia. After consultation with the Central Bureau of Fungal Cultures in the Netherlands, and given the absence of an available reference strain (the rhinoceros isolate from the 1930s having disappeared), he temporarily proposed the designation Pityrosporum canis.

His experiments demonstrated that inoculation of this yeast into healthy dogs induced a mild transient otitis, and that application of malt agar supplemented with olive oil into the auditory canal promoted Malassezia proliferation and the appearance of otitis. These observations allowed Gustafson to conclude that Pityrosporum canis represented a cause of otitis and that this condition could occur through activation of yeasts normally residing in the external auditory canal.

Seventy years later, scientific consensus fully confirms that M. pachydermatis constitutes a secondary opportunistic otic pathogen requiring some form of predisposition or pre-existing auricular abnormality to generate clinically significant otitis. Dr Gustafson had therefore correctly identified the fundamental mechanisms of this pathology as early as the mid-twentieth century.

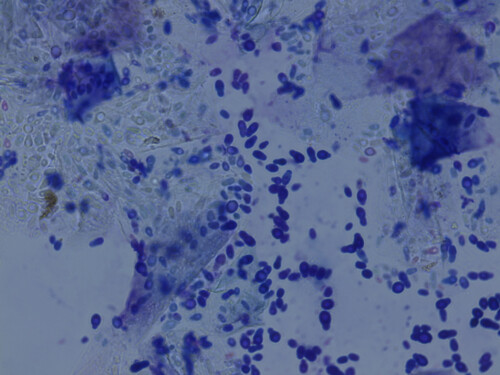

Classic appearance of Malassezia pachydermatis

History of Malassezia dermatitis

Regarding Malassezia dermatitis in dogs, the earliest reports are attributed to the Belgian practitioner Dufait, who published several articles in the late 1970s and early 1980s describing this condition. Professor Larson in Brazil also contributed by publishing case series documenting the clinical manifestations of this emerging pathology. Ken Mason then took up the torch by presenting these observations at various scientific meetings and professional conferences. The first mention of Malassezia dermatitis at an AAVD/NAVDF congress probably dates back to 1987 in Phoenix, Arizona, where Ken Mason presented an abstract describing three canine cases.

Recognition and clinical acceptance

This initial presentation elicited a mixed reception within the scientific community, with some practitioners remaining sceptical about the pathogenic relevance of this yeast in the dermatological context. Progressive acceptance of the clinical relevance of this yeast followed, and Malassezia dermatitis now forms an integral part of daily veterinary practice in small animal medicine on a global scale.

Taxonomic evolution and complexity of the genus

Origins of nomenclature

The genus Malassezia was first observed in 1846 and initially designated Cryptococcus. Malassez subsequently described these spores in cells from human dandruff, thus establishing the link between these organisms and desquamative conditions of the human scalp. The genus name Malassezia was proposed in recognition of this researcher’s work, then modified by Sabouraud to Pityrosporum, before being re-established in the 1980s in its original designation.

Lipid and morphological classification

The initial taxonomy was relatively simple and comprehensible: all Malassezia yeasts were recognised as lipophilic, and those strictly dependent on lipids, requiring special culture media supplemented with fatty substances, were grouped under the single species Malassezia furfur. Eminent mycologists of the era, such as Evelyn Guého and Gillian Midgley, nevertheless emphasised the existence of great morphological diversity within this group, distinguishing different oval forms designated as oval form 1, oval form 2, oval form 3, and so forth. The morphological diversity strongly suggested the existence of multiple distinct species within this taxonomic grouping initially considered monospecific.

Specificities of Malassezia pachydermatis

Malassezia pachydermatis, the predominant species in carnivores and undoubtedly the most relevant for veterinary practice, was classified as non-lipid-dependent as it could grow on Sabouraud Dextrose agar, the routine mycological culture medium. Human lipophilic species demonstrate their clinical importance in various dermatological conditions such as Pityriasis versicolor, characterised cytologically by the classic “spaghetti and meatballs” appearance of the pseudohyphal phase of what was formerly designated M. orbiculare, as well as in seborrhoeic dermatitis of the scalp.

Contribution of molecular mycology

The advent of molecular mycology techniques has considerably complicated the taxonomy of the genus. Complete genome sequencing of M. pachydermatis revealed that it actually belongs to the strictly lipid-dependent group, as it shares with other species the absence of the gene encoding fatty acid synthase. Its apparently paradoxical ability to grow on Sabouraud agar is explained by the sufficient presence of palmitic acid in the peptone component of this medium, an adequate quantity to support the growth of this species but insufficient for more demanding species. Other species require marked and substantial lipid supplementation for their laboratory culture.

Feline species and animal diversity

In cats, various strictly lipophilic species have been isolated in culture with subsequent molecular confirmation of colony identification, notably M. sympodialis, M. globosa, M. furfur, M. nana (particularly in the auditory canal) and M. slooffiae (notably in the nail folds). Rui Kano was the first to describe M. nana in cats and cattle, thus establishing the importance of this species in these animal populations. Other species are mainly associated with human skin in culture, whilst some are linked to specific animal hosts: M. caprae in goats, M. equina in horses, M. gallinae in chickens, and M. botryllophilus in bats. Distinction between these species cannot be achieved solely by culture; a molecular sequencing test remains necessary for precise and definitive identification. This growing taxonomic complexity raises important questions concerning the clinical relevance of this diversity of species. The ability to precisely identify the species involved in a given clinical case could potentially influence therapeutic decisions, particularly in the context of the emergence of antifungal resistance.

Cutaneous ecology and anatomical distribution

Mechanism of pathogenicity

The transition from a commensal status to that of pathogen is frequently observed when the homeostatic balance between host immunity and fungal virulence becomes disturbed, necessitating a targeted therapeutic approach associated with identification and correction of underlying predisposing factors.

Commensal colonisation in dogs

Malassezia pachydermatis constitutes a normal inhabitant of the skin and healthy mucosae of the dog, forming an integral part of the commensal cutaneous microbiome. A study on 40 healthy dogs conducted many years ago revealed a culture isolation frequency exceeding 30% in the auditory canal, confirming that this anatomical location represents a major reservoir of commensal colonisation. Conversely, the axilla, groin and dorsum presented an isolation rate of 10% or less, suggesting much more sporadic and limited colonisation of these sites. To detect this yeast on the skin of a healthy animal by cultural method, the preferred sites are the interdigital space and the lip region, where culture recovery rates prove significantly superior. Amongst mucosal sites, the anus represents the preferred location, with more than 50% of animals presenting detectable anal colonisation by culture. A temporal study with weekly sampling confirmed that the anus remains the site where the yeast persists most consistently over time, other sites showing more intermittent and variable colonisation.

Presence in the gastrointestinal tract

Unexpected and initially surprising observations have emerged concerning the presence of Malassezia in the gastrointestinal tract. A subsequent study conducted in collaboration with Arti Kathrani, specialist internist, and Bart Theelen, working at the time at the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute in the Netherlands (currently in Minnesota), involving 45 dogs with enteropathy undergoing endoscopy for various diagnostic investigations, permitted culture of Malassezia in eight of them, confirming preliminary observations and establishing the authentic presence of these yeasts in the canine small intestine.

Cutaneous microbiome and species diversity

Microbiome studies utilising molecular techniques have revealed an unexpected diversity of Malassezia species on canine skin, notably through DNA detection. Richard Harvey, renowned clinician and researcher, recently published a microbiome study conducted in collaboration with certain exhibitors present at veterinary conference commercial exhibitions. A study examining the umbilical region of 20 healthy dogs identified Cladosporium in all individuals and M. pachydermatis in only two of them, confirming the results of earlier classic culture studies. Conversely, DNA from M. sympodialis, M. restricta, M. slooffiae and M. arunalii was also detected by molecular methods. These observations contrast strikingly with culture results, constituting a particularly intriguing and scientifically troubling observation. Over 31 years of systematic culture of Malassezia from canine skin on lipid-supplemented media theoretically designed to support the growth of all Malassezia species, only one occasion permitted isolation of anything other than M. pachydermatis. Similarly, in the intestinal study mentioned previously, M. sympodialis was cultured only once from all samples.

Hypotheses on the molecular/culture divergence

This astounding divergence between molecular detection and culture raises several fundamental explanatory hypotheses: culture media might not be optimal for all demanding lipophilic species despite applied lipid supplementations, these species could be present in low numbers below the cultural detection threshold making their isolation unlikely, mixed microcolonies could exist with preferential persistence of M. pachydermatis during successive subcultures leading to loss of other more fragile species, or the detected DNA might not correspond to viable organisms but rather to genetic material from dead or damaged cells. Contamination of canine skin by human Malassezia DNA transferred through handling and contact also remains conceivable, particularly in a context where human-animal interactions are frequent and intimate.

Environmental observations

A particularly surprising recent discovery comes from a published study concerning vine leaves from Italian vineyards, where Cladosporium and Malassezia were identified as the most abundant fungi in this plant substrate. This observation proves unusual as Malassezia is not generally considered a plant organism but rather as an obligate inhabitant of mammalian skin, raising intriguing questions concerning the global ecology of this fungal genus.

Microbiome and atopic dermatitis

Cody Meason Smith, eminent mycologist working in collaboration with Dr Hoffman, published a remarkable array of studies on the canine cutaneous microbiome. In healthy laboratory dogs, molecular analyses show that M. restricta and M. globosa predominate, exactly as in healthy human skin. Conversely, in laboratory dogs experiencing flares of experimentally induced canine atopic dermatitis, M. pachydermatis and M. restricta become the most abundant in molecular analyses, with detection of more strictly lipophilic species also in the background.

The question of Malassezia globosa

This observation concerning M. globosa raises important clinical questions. M. globosa presents a characteristic spherical morphology with thick and prominent budding, distinct from the narrow bud observed in certain Candida species. Although round yeasts are sometimes observed in cytology, notably of auricular origin, they do not correspond to routine cytological observations in the majority of veterinary clinics. The question therefore remains: if M. globosa is important and present according to molecular studies, why is it not observed in routine cytology?

Culture limitations and contamination

Several explanations can be proposed for this apparent discordance. Current culture media, even those enriched with lipids such as modified Dixon agar, might not be sufficiently optimal to culture all these diverse Malassezia species with strict and varied nutritional requirements. These species could be present in insufficient number, below the detection threshold by traditional culture, not generating sufficient colonies to be noticed. The phenomenon of mixed microcolonies constitutes another plausible explanation. During successive subcultures of mixed colonies, M. pachydermatis, an easy-to-culture and fast-growing species, could persist whilst more demanding and slow-growing lipophilic species could progressively die and disappear. The molecular DNA detected indicates the presence of DNA but does not necessarily confirm the presence of viable and metabolically active organisms. Genetic material from dead or degraded cells could persist in the cutaneous environment and be detected by PCR amplification. Contamination of canine skin by human Malassezia DNA transferred through handling, stroking and close contact between owners and animals could also contribute to some of the observed molecular results. Technical methodological issues in microbiome studies, although outside the domain of dermatological expertise, could also influence results and their interpretation.

Climatic influence

Malassezia yeasts reside in the stratum corneum, at the level of what Bart Theelen, eminent mycologist, would call the transitional mantle zone, where they undergo the influence of climatic factors such as environmental heat and humidity. Dermatological practice in London, situated 4,400 miles north-east of the location of this conference, operates in a much cooler and much less humid climate than many North American regions. The mycological laboratory incubator functions as a humid incubator at 32 degrees Celsius, reproducing optimal conditions for yeast growth. Many dogs worldwide live in humid and warm environments, either year-round in tropical and subtropical regions, or during summer months in temperate regions. Dogs living in such climatic conditions, particularly those in the south-eastern United States, present an increased frequency of Malassezia proliferation according to reports from practitioners exercising in different geographical and climatic zones.

Interactions with host and bacteria

Yeasts in the stratum corneum are influenced by host chemistry and immune factors in the broad sense, including innate and adaptive immunity. They metabolise sebaceous lipids produced by sebaceous glands and lipids derived from keratinocytes, abundant substrates in the stratum corneum owing to their necessity for lipid-dependent yeast metabolism. Their interactions with commensal and pathogenic cutaneous bacteria remain poorly understood and constitute a domain requiring in-depth research. A recent publication indicated that certain lipophilic species of Malassezia present on human skin interact with Staphylococcus aureus and reduce its tendency to biofilm formation, suggesting a potentially beneficial role in regulating bacterial virulence and modulating cutaneous microbial ecology. These commensal yeasts could therefore exert protective effects by limiting the pathogenicity of other cutaneous microorganisms, adding further complexity to our understanding of cutaneous microbial ecology.

Pathogenesis and virulence mechanisms

Enzymatic production and metabolic activity

Fungi, nutritionally absorptive organisms, release a wide array of enzymes into their environment to create substrates assimilable by the fungal cell through the cell wall and cell membrane. These enzymes, particularly during marked and massive yeast proliferations, possess the potential to damage the host’s epidermal cells and activate innate and specific immune systems. The cell wall of Malassezia contains adhesion molecules facilitating adherence to corneous squames, a process that can be quantified by spending weeks microscopically counting Malassezia cells to determine whether they adhere to squames or not and to examine the molecular factors involved in this process. These yeasts present IgE-binding epitopes responsible for immediate hypersensitivity reactions and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), recognised by immune cells via C-type lectin receptors, as well as by T helper 17 cells. The growing importance of T helper 17 lymphocytes in fungal immunity, both innate and adaptive, is increasingly documented in contemporary scientific literature, although detailed immunological mechanisms exceed the domain of dermatological expertise and require consultation of specialised immunology literature for in-depth understanding.

Lipases and cutaneous biochemistry

In human medicine, fungal lipases play a recognised and well-established role in the development of dandruff and seborrhoeic dermatitis of the scalp. Aristea Velegraki and collaborators have demonstrated that lipoperoxidation of squalene generates metabolites recognised as biochemical markers of dandruff-affected skin, potentially involved in the pathogenesis of this condition. However, squalene does not represent a major component of canine sebum, unlike human sebum where it constitutes a substantial lipid fraction.

Enzymatic characterisation and phospholipases

Commercial kits such as API Zym permit characterisation of enzymatic activities of culture supernatant and cell pellet from a broth culture. Following centrifugation of the cell pellet from a broth culture, enzymatic activities can be detected in the test kit. Some enzymes appear associated with the cell pellet rather than the supernatant, whilst others are more abundant in the supernatant than in the cell, and some present equivalent levels in both fractions. M. pachydermatis produces a whole range of enzymes, including esterases and lipases. Phospholipase production proves particularly important in M. pachydermatis, with higher levels in strains associated with lesional skin compared with isolates from healthy skin, and in certain genotypes more associated with cutaneous conditions than with commensal colonisation.

Virulence and protein expression

The late Claudia Cafarchia, unfortunately recently deceased, and her research group demonstrated the importance of phospholipase production, showing superior enzymatic levels in pathogenic strains. Administration of azoles, fungistatic drugs, disrupts yeast enzymatic production, as do essential oils according to certain publications. Substantial proliferation of Malassezia therefore generates massive enzymatic production potentially involved in the pathogenesis of dermatitis and otitis. Recent work involving Thomas Dawson and various collaborators has emphasised the importance of studying fungal protein expression in physiologically relevant environments rather than in artificial laboratory conditions. A broth culture does not reproduce the physiological conditions of the stratum corneum, and protein expression of yeasts in this natural environment differs substantially from that obtained in artificial broth. These authors have developed sophisticated scientific techniques to demonstrate protein expression of yeasts directly in the stratum corneum, revealing expression profiles different from those observed in liquid culture.

Animal experiments and commensal-pathogen transition

Experiments on laboratory beagles have shown that daily application of Malassezia to the skin under occlusion for one week permitted creation of a local plaque of dermatitis with greasy brown exudate matting the hairs, similar to lesions observed in routine clinical practice. However, cessation of application led to complete healing within one week, demonstrating that normal skin therefore effectively controls its Malassezia population and does not develop infection through simple external application. This work was conducted under the Home Office Scientific Procedures Act, rigorous British legislation regulating the use of animals in an experimental scientific environment and guaranteeing animal welfare. An underlying alteration proves necessary to permit pathological yeast proliferation and the development of clinical signs. As clinicians recognise and understand well, normal skin does not simply become infected through yeast application. Something must be fundamentally altered to permit this commensal yeast to proliferate opportunistically and generate clinically significant disease.

Predisposing factors and underlying conditions

Diversity of triggering factors

Consensus guidelines have established a list of predisposing factors including breed, allergy, desquamation defects, endocrinopathies, skin folds, climate and unidentified cases. This list carries major clinical implications requiring in-depth understanding. In unidentified cases, representing the most frustrating category, the absence of understanding of the initial triggering factor prevents any correction and inevitably leads to chronic recurring and relapsing disease, generating intense frustration in the owner and necessitating continuous and repeated treatments without definitive resolution.

Allergy management

In the presence of allergy as a predisposing factor, complete elimination of yeasts by an antifungal, however effective it may be and even the best antifungal drug known to humans, does not suppress persistent residual allergic signs. If the sole criterion of therapeutic success for the owner is the complete disappearance of erythema and pruritus, short-term failure is inevitable and predictable, unless the owner is properly informed in a transparent manner of the partial response expected in these particular circumstances. The classic West Highland White Terrier out of control with conventional medications perfectly illustrates this situation: treatment of Malassezia and staphylococci reveals underlying atopic dermatitis which then becomes controllable with appropriate therapies. Primary cornification defects constitute a permanent and irreversible condition. The dog intrinsically possesses this keratinisation disorder and remains affected by it continuously. Skin folds persist unless dietary intervention permits their reduction through substantial weight loss or definitive surgical resection. If animals present anatomical folds, then these folds persist indefinitely unless made smaller through weight modification or surgically removed. Brachycephalics also constitute a particularly at-risk category, notably in the United Kingdom, where the prevalence of French Bulldogs has greatly increased.

The Basset Hound is frequently affected by Malassezia dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis and keratinisation disorders

Allergy, particularly atopic dermatitis, constitutes the predominant triggering factor in many veterinary hospitals. In certain specialist hospitals, 50% of Malassezia dermatitis cases present atopic dermatitis as the probable underlying trigger. A study using contact plates as a culture method conducted by students as part of a research project demonstrated that healthy animals presented low isolation frequency and very low Malassezia populations, whilst atopics showed significantly higher isolation frequency and populations on a statistical level. The blue-green column representing healthy animals on the graph shows low frequency and very low populations, whilst atopics in red demonstrate much more frequent isolations and considerably higher populations also.

Atopic Westie presenting with Malassezia dermatitis

Complications of atopic dermatitis

Complicated atopic dogs do not simply present pure and simple atopic dermatitis. In many cases, there is also secondary Malassezia dermatitis which considerably aggravates the overall clinical severity. Approximately two-thirds of atopic dogs develop superficial pyoderma problems and one-third develop a Malassezia dermatitis problem. Elizabeth Molterdin and colleagues published a very beautiful remarkable study in Veterinary Pathology a few years ago, referring to autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis observed in American Bulldogs. This study elegantly demonstrates that squamous puppies affected by this genetic keratinisation disorder become erythematous and pruritic when colonised by Malassezia, unlike healthy unaffected puppies which do not develop clinical signs despite similar exposure. The desquamation disorder therefore affects the epidermis in such a way as to favour opportunistic proliferation of Malassezia and the appearance of clinical signs of inflammation and pruritus.

Breed and anatomical predisposition

Certain breeds present a particularly marked predisposition to Malassezia dermatitis. The seborrhoeic Basset Hound constitutes the paradigmatic example, showing a median Malassezia population density in the axilla of the order of 10^5, representing 100,000 times higher than that of healthy mixed breed dogs used as a control group. Healthy Basset Hounds present intermediate populations, with substantial overlap between healthy and diseased individuals on distribution graphs. A substantial quantity of Malassezia can therefore be present on clinically normal-appearing skin, depending on the enzymes produced by the yeasts and the host’s cutaneous immunological reactivity.

Armpits are frequently affected by Malassezia dermatitis

Feline predisposition (Devon Rex, Sphynx)

In cats, the Devon Rex behaves like the Basset Hound in the feline world, representing the feline equivalent of this predisposed canine breed. These cats present marked susceptibility to Malassezia. A contact plate study in the axilla of cats demonstrates that moggy cats do not present much Malassezia, Cornish Rex do not present Malassezia, whilst seborrhoeic Devon Rex with black seborrhoeic deposit show growth on the contact plate. Healthy Devon Rex constitute an intermediate group between these extremes. Sphynx cats, closely genetically related to Devon Rex but lacking coat, frequently develop early-onset Malassezia otitis, often from a young age.

Anatomical zones at risk

Skin folds constitute anatomical predilection zones for Malassezia proliferation. The umbilical fold of entire female Basset Hounds represents a frequently affected location, often showing material adherent to hair shafts. Facial folds of brachycephalics, notably French Bulldogs whose prevalence has exploded in the United Kingdom and North America, represent frequent locations of Malassezia dermatitis. Although this situation constitutes a disaster for animal welfare due to multiple health problems affecting these extreme brachycephalic breeds, it paradoxically ensures the financial viability of many veterinary clinics by generating a significant volume of consultations and treatments.

Malassezia otitis: pathogenesis and microbial ecology

Transition from commensal to pathogenic flora

In the context of otitis, Malassezia acts as a secondary opportunistic pathogen, and the conceptual schema of otitis distinguishing predisposing, primary, secondary and perpetuating factors proves very useful for delineating all elements explaining problematic and refractory otological cases.

Quantitative analysis of auricular flora

Data from VP Hwang, one of Peter Hill’s former doctoral students, show the isolation frequency of various microbial species in otitis by quantitative culture. Coryneforms, coagulase-negative staphylococci and micrococci present in healthy animals progressively disappear in otitis cases, whilst simultaneously a transition occurs towards coagulase-positive staphylococcus infections and Gram-negative bacilli such as Proteus and Pseudomonas and similar organisms. In Hwee Peng Hwang’s study, there was a fairly high frequency of Malassezia isolation in normal animals, approximately 25%, although sometimes lower rates are reported in other studies. Gustafson in his original work reported frequencies below this percentage. A small frequency increase is observed in otitis cases compared with healthy animals. Quantitative analysis nevertheless reveals a major and fundamental difference concerning yeast population size. Twenty healthy dogs examined by semi-quantitative swab lavage method showed two dogs with a single Malassezia colony and 18 dogs without detectable auricular Malassezia. Diseased dogs from studies conducted recently with previous and current residents present a median population size of the order of 10^5, representing a 100,000-fold increase in population density in otitis cases with Malassezia proliferation compared with healthy ears.

Iatrogenic dysbiosis and therapeutic consequences

For many years, it has been observed that powerful antibacterial monotherapy, such as injectable enrofloxacin or piperacillin-tazobactam, effectively eliminates Pseudomonas in cases refractory to conventional treatments, but regularly creates Malassezia proliferation, or occasionally Candida. Piperacillin, a third-generation penicillin possessing extended activity against Gram-negative organisms, combined with tazobactam which blocks penicillinase like clavulanate in other formulations, permits resolution of desperate end-stage Pseudomonas otitis cases, but frequently generates subsequent yeast otitis.

Impact of antibiotics on flora

A study on 20 dogs currently being monitored attempts to prevent this iatrogenic complication. Data concerning piperacillin-tazobactam demonstrate similar results although even more marked than with injectable enrofloxacin, the latter being less effective against Pseudomonas and less frequently generating subsequent yeast dysbiosis. These animals do extremely well clinically when administered piperacillin and tazobactam for their bacterial otitis, but regularly develop Malassezia proliferation requiring additional antifungal treatment.

Clinical manifestations

Dermatological signs in dogs

Clinical manifestations of canine Malassezia dermatitis are varied and characteristic. A young Scottish Terrier may begin its existence with chronic dermatitis characterised by symmetrical lesions at the level of the medial thigh and groin, in the form of fairly well-delimited plaques of alopecia. A Jack Russell Terrier more advanced in disease evolution presents marked excoriation and lichenification testifying to chronicity and persistence of the inflammatory process.

Basset Hounds frequently show material adherent to hair shafts at the level of the umbilical fold. This brownish or blackish material is also found in the interdigital spaces. This clinical characteristic proves diagnostically useful, as if atopic dogs, dogs infested with Trombicula (harvest mites) or affected by demodicosis present interdigital erythema, only those carrying yeasts or staphylococci develop this characteristic kerato-sebaceous debris. The neck fold of very malodorous and inflamed Basset Hounds shows similar deposits of kerato-sebaceous material.

Typical symptomatology: pruritus and odour

Clinical signs include pruritus, erythema, scales and greasy seborrhoea, pigmentation, lichenification, and of course, the characteristic unpleasant malodour which accompanies some of these animals and permeates consultation rooms. Paronychia with periungual crusts and brown nail discolouration can occur. Sometimes, coloured material may be superficial and can be mechanically removed; other times the stain seems to be somehow deeply impregnated into the claw keratin in a more permanent manner. Unusually frenzied muzzle pruritus constitutes another intriguing clinical manifestation.

Feline particularities

Cats are not small dogs, and this fundamental statement remains true concerning Malassezia dermatitis. Allergic cats presenting with intense cervicofacial pruritus can develop Malassezia dermatitis, although less frequently than dogs. The Rex cat represents the Basset Hound of the feline world in terms of predisposition to Malassezia. Devon Rex show marked susceptibility, with presence of brownish material on the abdomen and medial thigh, and blackish debris in the interdigital spaces and nail folds. Sphynx cats, closely genetically related to Devon Rex but lacking coat, develop early-onset Malassezia otitis.

Feline paraneoplastic syndromes

Some practitioners have encountered pancreatic paraneoplastic alopecia in older cats, a dramatic and characteristic syndrome. Sudden weight loss in an elderly cat with sudden onset of dramatic, symmetrical and complete alopecia, sometimes accompanied by a blackish deposit. Another illustrative case shows the shiny skin associated with loss of stratum corneum, a fairly distinctive characteristic of this syndrome, and the brown deposit of secondary Malassezia dermatitis.

Exfoliative dermatitis and thymoma

Another cat was seen by several specialist residents a few years ago. Kathy Bortnick, dermatology resident, collected a few contact plates for mycological analysis. This cat presented exfoliative dermatitis caused by a thymoma, thymic tumour. Contact plate cultures showed Malassezia growth. Rob, soft tissue surgery resident and pragmatic visual surgeon, surgically removed the thymus. Kathy prescribed two selenium sulphide shampoo baths. All the Malassezia disappeared completely. Surgical resection of the thymus combined with simple topical therapy totally eliminated yeast proliferation. The paraneoplastic problem and desquamation disorder being controlled, Malassezia dermatitis disappeared. The major difference between cat and dog resides in the frequency of association with serious systemic conditions, notably visceral neoplasias and metabolic diseases, triggering Malassezia as a new manifestation in an elderly animal. This eventuality necessitates particular vigilance and thorough investigation upon sudden appearance of Malassezia proliferation in a previously healthy cat.

Diagnostic approaches

Quantification and detection methods

Malassezia quantification on the skin and understanding its clinical relevance constitute complex diagnostic challenges.

Contact plate vs Cup scraping

Contact plates represent a simple but widely underutilised method. They are manufactured from bottle lids filled to the brim with culture medium, maintained in sterile Petri dishes to preserve sterility. Direct application to a cutaneous lesion for 10 seconds, followed by three days’ incubation at appropriate temperature, permits appreciation of yeast abundance through observation of confluent or scattered growth. For cats, smaller lids of reduced dimensions apply easily in interdigital spaces and other restricted anatomical sites. Cup scraping definitely constitutes essentially a research tool rather than routine clinical practice. This technique requires flat skin and a cooperative patient, conditions not always met in practice. A sterile Teflon cup containing 2 ml of physiological saline with added detergent permits gentle rubbing of the targeted skin. The aspirated liquid undergoes serial dilutions until obtaining a countable number of colonies after culture, permitting extrapolation of a population density expressed in colony-forming units per square centimetre. Yeasts die rapidly in physiological saline with detergent, requiring immediate sample processing, incompatible with postal dispatch or prolonged transport delay. Contact plate counts and cup scraping are not well correlated statistically. Adhesive tape counts are not correlated with cup scraping either. A methodological problem therefore exists. The reference method for culture of Malassezia, it could be argued, remains cup scraping as the gold standard, but daily clinical practice commonly uses adhesive tape or similar more practical techniques.

Cytology and clinical interpretation

The adhesive tape technique, popularised by the historic publication of Keddie and Libis in Sabouraudia, permits diagnosis of microbes residing in the stratum corneum. In the United Kingdom, Scotch or Sellotape Diamond Clear are commonly used, different commercial brands surviving or not the staining process depending on their composition. A practical method presented by our colleague consists of fixing a piece of adhesive tape to the end of a glass slide, creating an assembly manipulable with one hand. This hand can separate the interdigital spaces or separate the labial fold or facial fold, permitting slide insertion, squame harvesting, then rapid Diff-Quik staining after tape rolling and flattening on the slide.

Factors influencing counts

The significance of counts depends on multiple factors. The sampling method fundamentally influences results. Dry scraping and direct impression generally do not provide sufficient material transfer compared with ‘tape stripping‘, although other practitioners may have different perspectives. The anatomical site constitutes a major factor. Contact plate counts from lips and foot differ significantly. There are more yeasts in a labial fold in a healthy dog compared with the interdigital space. How to determine which population threshold constitutes pathological proliferation if the normal population varies substantially from one anatomical site to another?

Breed influence on populations

Breed considerably influences normal populations. Healthy mixed breed dogs present few yeasts, and when they possess them, populations remain very low. Seborrhoeic Basset Hounds show a median population density much higher than healthy mixed breed dogs.

Cytological thresholds and research

In cats, a contact plate study in the axilla demonstrates that moggy cats do not possess much Malassezia. Cornish Rex do not present Malassezia. Seborrhoeic Devon Rex with blackish deposit show growth on the contact plate. Healthy Devon Rex constitute an intermediate group between these extremes.

Immune status and hypersensitivity

The host’s immune status plays a crucial role in count interpretation. Some animals present detectable immediate hypersensitivity by IgE test, by serology or intradermal tests. Others show delayed hypersensitivity upon intradermal testing. In Basset Hounds, contact hypersensitivity correlates well with disease or its absence. Healthy Basset Hounds do not show contact hypersensitivity, unlike diseased ones which develop it, if the effort to perform patch tests on dogs is made, a procedure not adapted to daily clinical routine. As for other allergens, the IgE test constitutes precisely that: an IgE test. If an intradermal test is performed, it is not a disease test but an immunological sensitivity test. A healthy Basset Hound presenting spectacular and dramatic immediate hypersensitivity to Malassezia upon intradermal testing illustrates this dissociation between sensitivity and clinical disease.

Histopathology

Histopathology can be performed to document Malassezia dermatitis lesions. It is probably not the best method to search for something residing in the stratum corneum owing to the substantial disruption which occurs in normal formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded sections according to standard histological protocols. On a comparative slide, normal stratum corneum shows the common basket-weave orthokeratosis that pathologists would routinely observe. Conversely, in a cryostat section – technically difficult to perform, cutting skin in a cryostat representing a technical challenge – observation reveals how much the good barrier, the intact stratum corneum, is densely packed with a large stacking of squames constituting a compact barrier. This is a processing artefact, it is absolutely not like that in real life in vivo. In a scanning electron micrograph, the large stacking of squames forming the usual barrier is visible. The lipid seal is missing, removed and eliminated by sample preparation processing, but the large stacking of squames persists.

Artefacts and histological observations

When a dog biopsy is examined and shows all this absent stratum corneum or all this loose and disorganised material, it is a histological artefact and not a faithful representation of the structure in vivo. Some important features can nevertheless be observed, including irregular epidermal hyperplasia of the interfollicular epidermis extending into the follicular infundibulum. Keratosis is certainly present. A degree of oedema and a superficial perivascular or interstitial dermal infiltrate characterise the lesions. Owing to the substantial disruption of the surface stratum corneum during histological processing, a good place to search for Malassezia resides in the follicular ostia or infundibula, structures less disrupted than the superficial stratum corneum. In a standard haematoxylin-eosin (H&E) stained specimen, if this area is examined at higher magnification, the yeasts become visible. Although these organisms can be visualised with standard H&E staining, they can be cleared and rendered more evident with PAS (periodic acid Schiff) staining and even better highlighted with silver staining if necessary for confirmation.

Key histopathological characteristics

Histopathological characteristics described by various authors and documented are fairly concise. Keratosis, either orthokeratotic or parakeratotic, epidermal hyperplasia, spongiosis, lymphocytic or neutrophilic exocytosis and a lymphocytic or mixed dermal infiltrate. Histopathology in cats remains less well defined and documented. Hyperkeratosis and hyperplasia constitute important features, but characteristics of the underlying disease triggering Malassezia proliferation could also be observed in histological specimens.

Diagnostic algorithm

Step-by-step approach

The approach to a suspected Malassezia dermatitis case logically begins with detailed history and identification of clinical signs compatible with this condition. The next step consists of demonstrating whether the yeast is present or not. This will normally be done by cytology in daily clinical practice, although in a research environment this may be performed by culture, quantitative culture permitting precise population assessment. Counts do not necessarily need to be high to justify treatment. If yeasts are detected in reasonable number, a trial therapy must be initiated and the response carefully observed. In their absence during initial sampling, re-sampling of additional sites or consideration of another diagnostic explanation is required.

Interpretation of therapeutic response

If yeasts disappear totally and clinical signs resolve completely, the diagnosis of Malassezia dermatitis is established with confidence and the search for an underlying cause becomes a priority to prevent recurrences. If yeasts disappear totally with partial overall clinical improvement, the diagnosis of Malassezia dermatitis is confirmed and investigation then treatment of residual allergy, desquamation disorder or anatomical fold problem must be undertaken. The classic West Highland White Terrier out of control with conventional medications perfectly illustrates this situation: treatment of Malassezia and staphylococci reveals underlying atopic dermatitis which then becomes controllable with appropriate therapies for allergic management. If yeasts disappear without any clinical benefit, their presence was incidental and not causal. Partial disappearance of yeasts with partial clinical improvement suggests Malassezia dermatitis, requiring review of therapeutic compliance, extension and intensification of treatment to obtain complete yeast elimination. Total absence of clinical improvement with persistence of yeasts requires rigorous verification of owner compliance, treatment review and modification, and serious consideration of potential antifungal resistance, particularly in the contemporary context of emergence of resistant strains.

Therapeutic strategies

Systemic treatment in dogs

Efficacy studies are reported for ketoconazole, itraconazole and fluconazole as azoles, as well as terbinafine as an allylamine. Some studies associated concomitant cefalexin owing to the importance of staphylococci in certain geographical and regional areas. Final choice will depend on local availability, local prescribing rules and pharmaceutical regulations, individual patient factors including comorbidities and contraindications, and costs which can vary considerably from country to country. Itraconazole and ketoconazole constitute valid options for administering to a dog with Malassezia dermatitis. Fluconazole has its supporters and advocates. It is the least active in the laboratory in terms of microgrammes per millilitre in minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) tests. Terbinafine requires more thorough evaluation. Concentrations in the stratum corneum at currently used doses might not be sufficiently high according to a published pharmacokinetic study.

Topical treatment in dogs

Efficacy data for topicals concern miconazole-chlorhexidine shampoo, 3% chlorhexidine shampoos, miconazole conditioners, and an essential oil-based product called MalAcetic. Two randomised controlled blind studies demonstrate good clinical activity of miconazole-chlorhexidine shampoo. Clinical trials on Malaseb (Miconazole-Chlorhexidine) conducted in July 1994 showed remarkable results. These dogs severely affected by Malassezia dermatitis, initially judged to require systemic ketoconazole and antibacterial cefalexin according to initial clinical evaluation, received only Malaseb shampoo as sole treatment at three-day intervals for three weeks.

Simultaneous elimination of staphylococci and Malassezia with this product proves important as some electron microscopies of some cup scraping samples reveal yeasts integrated but surrounded by numerous bacterial cocci, underlining the importance of simultaneously targeting staphylococci and Malassezia in these mixed infections. Based on methodical examination of published studies, miconazole-chlorhexidine represents the first-choice topical treatment assuming the animal accepts it and tolerates baths and that the owner can apply it correctly and regularly.

Auricular treatment in dogs

Otitis externa due to Malassezia pachydermatis in dogs constitutes a frequent condition requiring adapted topical antifungal treatment. On the market, several veterinary specialities are currently found based principally on two families of antifungals: azole derivatives and allylamines. Amongst commonly used therapeutic approaches, associations of miconazole with gentamicin and hydrocortisone aceponate are found, indicated in the treatment of acute and recurrent otitis externa due to azole-sensitive fungi. Other classic formulations combine clotrimazole, gentamicin and betamethasone for otitis of bacterial and fungal origin. Florfenicol and terbinafine associations specifically target mixed infections with Staphylococcus pseudintermedius and Malassezia pachydermatis. These polyvalent formulations systematically associate antibiotic, antifungal and corticosteroid, which limits the possibilities for specific treatment.chvsm+3

A recent therapeutic innovation on the French market constitutes the first long-acting auricular topical without antibiotic specifically developed for Malassezia pachydermatis otitis. This original formulation combines 10 mg of terbinafine, a fungicidal allylamine inhibiting membrane ergosterol synthesis, and 1 mg of betamethasone acetate for its anti-inflammatory action. The long-acting gel format permits a single application facilitating therapeutic compliance. Sensitivity studies conducted between 2021 and 2023 on European Malassezia isolates established MIC50 and MIC90 of 0.12 and 0.25 μg/ml respectively for terbinafine. This speciality fits into a reasoned antibiotherapy approach by offering an alternative without systematic antibiotic, particularly relevant for purely fungal otitis not requiring antibacterial coverage.

Treatment in cats

In cats, several uncontrolled open studies used itraconazole at doses between 5 and 10 mg/kg once daily, either continuously daily, or according to an intermittent protocol seven days with treatment, seven days without treatment, seven days with treatment, corresponding to the Itrafungol licence for dermatophytosis in the United Kingdom. Data remain limited for cats in general. The first-choice systemic azole would be itraconazole according to clinical consensus. Ketoconazole is probably not administered to any cat owing to concerns regarding tolerance and safety. Topical therapy also lacks rigorous scientific data.

Prevention and relapse management

Specific immunotherapy

Discovery and correction of underlying diseases constitute the absolute cornerstone of relapse prevention. A pulsed dosage, either topical or systemic, can be considered when everything else fails, with constant concern regarding antifungal resistance. Evidence for allergen-specific immunotherapy for Malassezia is lacking, although many practitioners use it routinely. During a previous discussion, it was established that many participants include Malassezia in their intradermal test panels and incorporate it into their immunotherapy formulations upon positive reactivity. In the absence of convincing and rigorous evidence, inclusion of Malassezia in allergen-specific immunotherapy rests more on expert consensus than on robust supporting data.

Maintenance strategies

The rational approach for an animal hypersensitive to Malassezia consists of minimising antigenic challenge by maintaining yeast populations low, as low as possible. This could mean very regular and assiduous topical therapy if animals can be bathed and owners can accomplish this task repetitively. This could mean pulsed azoles administered intermittently, but of course, legitimate concern exists regarding promoting antifungal resistance.

Antifungal resistance: mechanisms and issues

There are growing and concerning reports of the development of resistance to antifungal drugs but with heterogeneous distribution, principally described with the azole class, which are used routinely and globally in the treatment of canine Malassezia infections. It is endemic and frequent in certain East Asian regions, but remains sporadic in Europe and North America. Unfortunately, antifungal resistance surveillance lags substantially behind that performed for bacterial pathogens. This situation stems partly from a lack of standardised laboratory methods and infrequent submissions of samples for culture and sensitivity testing. Resistance in Malassezia and other fungi, as well as in human pathogens, constitutes an absolute major concern. Standard methods for yeast sensitivity testing are optimised by organisations such as CLSI (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute) in the United States and EUCAST (European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing) in Europe, optimised specifically for Candida and Cryptococcus. This focus, given the considerable importance of these pathogens in human medicine, is entirely justified and understandable. However, the tissue culture medium RPMI 1640 they recommend for this testing process does not support Malassezia growth. From this fundamental point, everything becomes improvised and non-standardised. No appropriate validated protocol exists for Malassezia.

Therapeutic alternatives and ongoing research

Innovative and natural products

Legitimate concerns regarding drug resistance stimulate efforts to identify effective treatments beyond conventional azole and allylamine antifungals. Nowadays, over the last seven to eight years, many studies have been conducted using all sorts of different non-azole, non-terbinafine things to try to kill Malassezia in vitro. Most of these approaches have been done in vitro and have not been extended to a rigorous randomised controlled trial on actual patients. Recent studies on otitis examine different innovative products: an auricular cleanser containing pomegranate as active ingredient, a plant-based product for treating otitis, an auricular rinse based on Norwegian spruce resin, then a more conventional product containing posaconazole, which is of course a large-calibre and very powerful azole antifungal. A few studies on dermatitis examine shampoos containing colloidal silver and sprays containing benzoyl peroxide and alcohol and various botanical oils. A silver nanoparticle shampoo showed promising results in a methodologically limited non-randomised open study. In vitro reports describe efficacy against M. pachydermatis of a honey-based gel, monensin and, to a lesser extent, narasin. These polyether ionophores were originally marketed as anticoccidials for poultry and as growth-promoting modifiers of bovine ruminal flora, and apparently present in vitro antifungal activity.

Essential oils and limitations

Multiple recent publications explore the potential antifungal utility of essential oils, complex mixtures of highly concentrated aromatic oils (principally terpenes and/or phenylpropanoids) extracted from plants by steam distillation, hydrodiffusion or mechanical pressure. Most investigations have been conducted in vitro and their actual utility in clinical practice remains largely untested clinically. Comparisons between studies are hampered and rendered difficult by the absence of optimised and validated standard testing methods, arbitrary attribution of interpretative criteria without rigorous validation, and probable variation between different batches of essential oil activities prepared by different extraction methods and from variable plant sources. The overwhelming majority of these alternative approaches have been carried out in vitro in test tubes without extension to randomised controlled clinical trials on real patients with rigorous clinical efficacy assessment.

Practical recommendations and perspectives

Cytology should be performed systematically in routine canine practice to search for these opportunistic yeasts and establish or refute their involvement in the clinical picture.

If the yeast is treated, precise counting is probably not necessary. Simply find it in reasonable number with compatible clinical signs, treat it and observe the clinical response. Follow patients with regular re-evaluations and repeat cytology and see if the yeast has disappeared and assess this against the observed clinical response. Treatment must be individualised according to different patient circumstances including comorbidities and contraindications, and owner circumstances including financial capacity and probable compliance. Certainly a systemic azole constitutes a valid option for cases that cannot be shampooed and other situations where topicals are impractical. Throughout the therapeutic process, one must constantly try to find and correct the underlying triggering factor because if this can be accomplished, recurrent infections can be reduced, the need for antifungal drugs can be reduced, and therefore the selection pressure which could lead towards the emergence and spread of resistance can be minimised.

Conclusion

Over the last 35 years, a remarkable expansion of knowledge concerning Malassezia-related skin conditions in dogs and cats has been achieved. Most veterinary practitioners are now comfortable recognising the varied clinical presentations of Malassezia dermatitis and otitis and observing the characteristic yeasts in routine cytology. The necessity of assessing and correcting, as far as possible, predisposing factors and underlying conditions is well understood by the contemporary veterinary community.

The concerning emergence of azole resistance amongst Malassezia species requires careful and continuous monitoring as well as rigorous management of these pharmaceutical products to guarantee the continued utility of this important drug class for decades to come. Development of appropriate standardised antifungal sensitivity tests validated for use by commercial and clinical microbiology laboratories is absolutely critical and urgent. Additional data are urgently needed to definitively establish whether topical therapies are preferable to systemic treatments in the context of resistance prevention, and to guide antimicrobial stewardship policies concerning antifungal therapy in small animal veterinary practice.

Bond R. Malassezia review Parts i and ii: Clinical signs, Diagnosis, therapy and resistance. NAVDF 2025 Meeting